The Research Brief is a short take about interesting academic work.

The big idea

People who care for friends, children or other loved ones may avoid products and services that make caregiving easier – such as ready-made meals – because they believe that doing so undermines their ability to show that they care, according to our new research. Psychologically, people equate effort with love, and taking shortcuts can make them feel guilty.

While making caregiving easier might seem like a good thing, people don’t necessarily perceive it that way. As part of our research, we collected Instagram and Facebook comments on posts about the SNOO, a smart crib that automatically rocks a fussy baby to sleep. We found that a plurality of the 675 comments we examined – 40% – were negative. Many of the comments called parents who would buy the SNOO “just lazy” or questioned them with such comments as, “If you need that device, you shouldn’t have kids.”

In fact, the more people perceived the SNOO as making bedtime easier, the more harshly they judged parents who used it.

These comments suggest that people have the intuition that proper caregiving should require effort. But does this intuition affect people’s own caregiving decisions?

We conducted nine experiments to answer this question.

Our first four experiments sought to tease out how important perceived effort is when caring for loved ones and whether people believe using an effort-saving product implies they don’t care enough.

For example, in one study, we recruited 251 undergraduate students and asked them to send their grandparents a card to cheer them up, which we mailed for them. We asked half of the students to pick one from a set of several premade cards, while the others made one themselves using markers, stickers and glitter. After they finished choosing or making a card, we asked how they felt. Students who used a premade card reported they felt like less dedicated family members and guiltier than those who sent a handmade one.

The next four studies examined when and with whom people felt it is especially important to express their love through effort.

In one study, we found that people making cookies to comfort their partner during the COVID-19 pandemic were over 20% more likely to choose to mix the dough by hand rather than use ready-to-bake frozen dough than those who were baking cookies to comfort themselves.

Overall, making an effort seemed most important when participants were trying to give emotional support or helping someone they were especially close to.

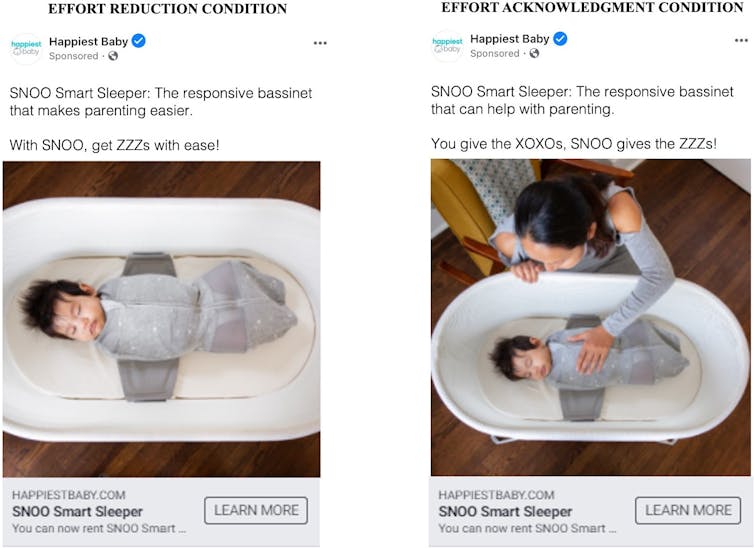

In our final study, we tested how companies offering products that support caregiving can make them more palatable to customers by teaming up with smart crib-maker Happiest Baby on an actual marketing campaign. We crafted advertisements for the company that described the SNOO in two different ways: by acknowledging parents’ efforts (“you give the XOXOs, SNOO gives the ZZZs”) or by emphasizing how the SNOO makes parenting easier (“with SNOO, get ZZZ’s with ease”).

After a two-week social media campaign, twice as many people clicked on the ad acknowledging parents’ efforts compared with the one that emphasized how much it reduced effort.

Why it matters

Caring for one’s family and friends is important and meaningful – but a lot of work.

People in caregiving roles say they experience high levels of stress and have very busy schedules. This has been especially true during the pandemic.

Yet our work suggests that people may not take advantage of ways to make this work easier – and when they do, they feel as if they are doing a worse job.

What still isn’t known

We didn’t test whether there are other ways people could be convinced that it’s OK to use effort-saving products to help them care for their family and friends.

Future work could examine exactly how caregivers prioritize showing their love versus getting tasks done when they are juggling multiple responsibilities for the many people in their lives. This could show how caregivers might feel enabled to show their love without spreading themselves too thin.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

* This article was originally published at The Conversation

HELP STOP THE SPREAD OF FAKE NEWS!

SHARE our articles and like our Facebook page and follow us on Twitter!

0 Comments