In 2021, an investigation revealed that home loan algorithms systematically discriminate against qualified minority applicants. Unfortunately, stories of dubious profit-driven data uses like this are all too common.

Meanwhile, laws often impede nonprofits and public health agencies from using similar data – like credit and financial data – to alleviate inequities or improve people’s well-being.

Legal data limitations have even been a factor in the fight against the coronavirus. Health and behavioral data is critical to combating the COVID-19 pandemic, but public health agencies have often been unable to access important information – including government and consumer data – to fight the virus.

We are faculty at the school of public health and the law school at Texas A&M University with expertise in health information regulation, data science and online contracts.

U.S. data protection laws often widely permit using data for profit but are more restrictive of socially beneficial uses. We wanted to ask a simple question: Do U.S. privacy laws actually protect data in the ways that Americans want? Using a national survey, we found that the public’s preferences are inconsistent with the restrictions imposed by U.S. privacy laws.

What does the U.S. public think about data privacy?

When we talk about data, we generally mean the information that is collected when people receive services or buy things in a digital society, including information on health, education and consumer history. At their core, data protection laws are concerned with three questions: What data should be protected? Who can use the data? And what can someone do with the data?

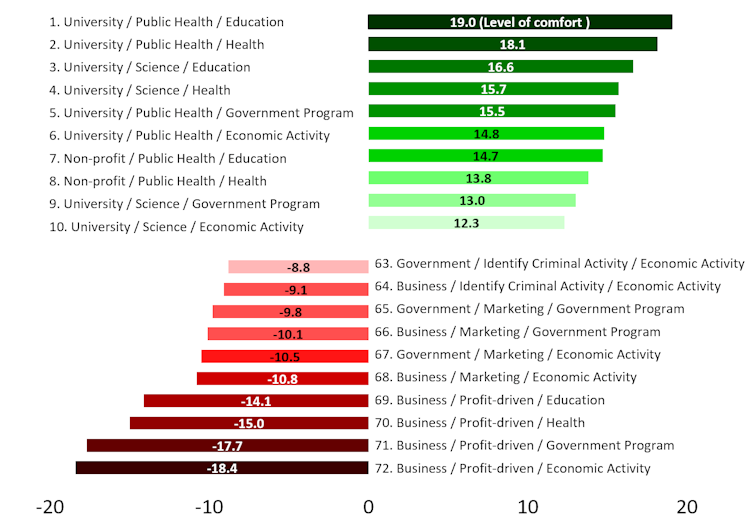

Our team conducted a survey of over 500 U.S. residents to find out what uses people are most comfortable with. We presented participants with pairs of 72 different data use scenarios. For example, are you more comfortable with a business using education data for marketing or a government using economic activity data for research? In each case, we asked participants which scenario they were more comfortable with. We then compared those preferences with U.S. law – particularly in terms of types of data being used, who is using that data, and how.

Under U.S. law, the type of data matters tremendously in determining which rules apply. For example, health data is heavily regulated, while shopping data is not.

But surprisingly, we found that the type of data companies or organizations use was not particularly important to U.S. residents. Far more important was what the data was being used for, and by whom.

The public was most comfortable with groups using data for public health or research purposes. The public was also comfortable with the idea of universities or nonprofits using data as opposed to businesses or governments. They were less comfortable with organizations using data for profit-driven or law enforcement purposes. The public was least comfortable with businesses using economic data to increase profits – a use that is widespread and loosely regulated.

Overall, our results show that the public tends to be more comfortable with altruistic uses of personal data as opposed to self-serving data uses. The law more or less promotes the opposite.

What’s allowed, what’s not

Ideally, data protection laws would limit the most risky data uses while permitting or even promoting beneficial, low risk activities. However, this is not always true.

For example, one federal law prevents sharing records of substance abuse treatment without an individual’s consent. It is, of course, beneficial in many cases to protect these sensitive records. However, during the ongoing opioid epidemic, these records could provide critical information on where and how to intervene to prevent overdose deaths. Worse yet, when only certain data is withheld for privacy, the remaining data can actually mislead researchers to make the wrong conclusions.

Sometimes, laws permit data use in ways that the U.S. public finds troubling. In most U.S. business contexts, using personal information for profit – for example, a company using personal information to predict customers’ pregnancies – is legal if this action is covered by a company’s privacy notice.

The American public’s awareness of and uneasiness with how companies use personal information has pushed lawmakers to explore new data regulations. Experts have argued that the status quo – a confusing patchwork of privacy laws – is inadequate, and some have argued for comprehensive privacy laws.

In the absence of federal legislation, some states have voted to put more comprehensive laws into place. California did in 2018 and 2020, Virginia and Colorado in 2021, and other states are likely to follow suit. If new laws are going on the books, we believe it is vitally important that the public has a say on what data uses should be restricted and which should be permitted.

How would good data privacy laws help?

Every year, hundreds of thousands of Americans die because of social factors like education, poverty, racism and inequality, and there are protected data sets that public health officials, researchers and policymakers could use to promote the common good.

The data-use case with the most public support is when researchers use education data for public health. Importantly, research shows that nearly 250,000 U.S. deaths annually can be attributed to low education – for example, a person having less than a high school diploma – and low education can contribute to poor nutrition, housing and work environments. But federal education privacy law limits groups from accessing education records for public health or any health research. In this case, U.S. data protection laws severely restrict researchers’ ability to understand these deaths or how to prevent them.

The data exists to better understand many other complex problems – like racism, obesity and opioid abuse – but data protection laws often get in the way of health authorities or researchers who want to use it.

Our research suggests that current legal barriers that prevent using data for the common good stand in stark contrast to the public’s wishes. As laws are revised or put into place, they could be designed to represent the public’s desires and facilitate research and public health. Until then, U.S. data privacy laws will continue to favor profit over the public good.

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter.]

In 2018 and 2020, Cason Schmit received funding from Data Across Sectors for Health (DASH) to study legal barriers to data sharing for population health.

Before 2016, Brian N. Larson was outside counsel and consultant to trade associations and their members active in consumer-facing online information systems in the residential real estate industry.

Hye-Chung Kum does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

* This article was originally published at The Conversation

HELP STOP THE SPREAD OF FAKE NEWS!

SHARE our articles and like our Facebook page and follow us on Twitter!

0 Comments