A few hundred feet south of the University of Mississippi’s famed Grove – site of bucolic commencement ceremonies and college football’s most unique tailgating experience – sits a nondescript red brick building, dwarfed by two enormous science complexes. Dating to 1908, the original two-story structure once housed a power plant that generated electricity for the campus and adjacent community of Oxford.

With the building slated to be torn down in 2016, it’s perhaps fitting to recount a unique moment in the power plant’s history – when it was the unlikely birthplace of one of 20th-century literature’s signature works.

In the autumn of 1929, 32-year-old William Faulkner was a newlywed who had recently moved out of his parents’ house on the University of Mississippi’s campus to a rented apartment a few blocks away. Though he’d published three novels, none had earned him much in the way of royalties. Nor had he cracked the lucrative national market for short stories in magazines like The Saturday Evening Post.

With a wife, Estelle, and two young stepchildren to support and insufficient literary income to do it, he took a job as a coal passer on the night shift at the power plant. As he described the work, “I shoveled coal from the bunker into a wheelbarrow and wheeled it in and dumped it where the fireman could put it into the boiler.”

By around midnight, power demand had dwindled and the work became less onerous. “Then we could rest, the fireman and I,” Faulkner wrote.

Yet rather than whittle away the hours dozing, Faulkner elected to “rest” by beginning a new novel. Using a wheelbarrow as a table – “just beyond a wall from where a dynamo [electrical generator] ran” – he would work on the manuscript “between 12 and 4,” until electricity use would pick up.

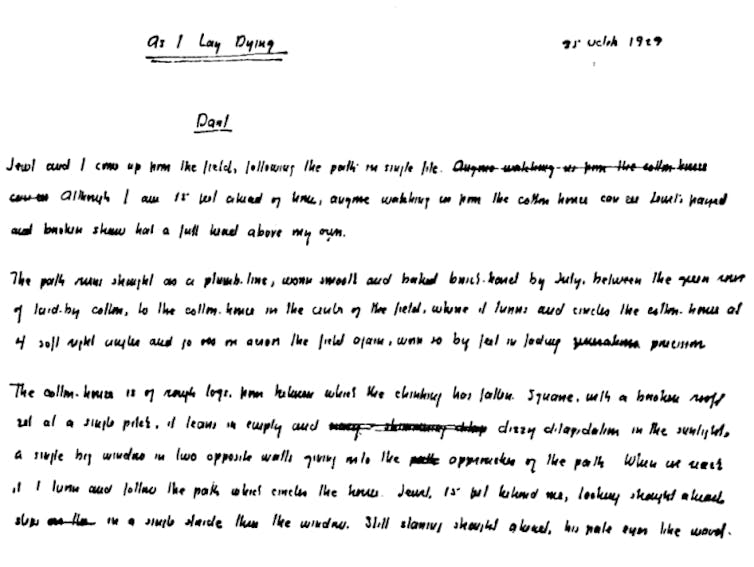

In only six weeks, he completed the entire manuscript, which he titled “As I Lay Dying.”

The novel, along with “The Sound and the Fury,” which was published later that fall, would establish Faulkner’s reputation as a modernist master.

The first page of the manuscript of “As I Lay Dying” bears the suggestive date of October 25, 1929. As it happens, this was the day after the infamous “Black Thursday,” when the US stock market collapsed, plunging the nation into economic crisis. For this reason, a case can be made for the novel as the inaugural American literary work of the Great Depression.

It was fitting that “As I Lay Dying” was the first time Faulkner placed the plight of the poor at the narrative center of a work. In earlier novels Faulkner had written about Great War veterans, pretentious intellectuals, professional people and plantation elites.

Here, however, he turned to the struggles of a white working-class family, the Bundrens, as they journey from their rural farm to the town of Jefferson, Mississippi, to bury the family matriarch, Addie. Their difficulties are compounded by midsummer heat, a flood-swollen river, and the contempt of local townspeople for country folk. Along with the trauma of loss and mourning, we witness the surviving Bundrens’ efforts – unforgettably rendered in their own voices – to understand the economic forces responsible for their marginal social position. In this way, the text links the family’s hardships to the larger forces responsible for the nation’s own economic crisis.

Yet crisis and grief can’t tell the whole story of Faulkner’s engagement with modernity in “As I Lay Dying.”

There’s also the dynamo to reckon with – that mechanical manifestation of technological progress. After all, it was the power plant that supplied the soundtrack for the composition of the novel. As Faulkner noted, the dynamo “made a deep, constant, humming noise.”

Was this the energy that found its correlative in the astonishing creative energy Faulkner brought to “As I Lay Dying?” In the brilliant blend of the vernacular speech patterns of southern rural people, with the strangeness and poetry of their inner lives? In his archetypal, hallucinatory imagery of fire and flood? In the interior monologue and stream of consciousness techniques he would later introduce in The Sound and the Fury?

Where a half-century earlier Henry Adams had recoiled from the dynamo’s implications as an emblem of modernity, Faulkner embraced them – indeed, emulated them – drafting his manuscript with breakneck speed, on a writing schedule dictated by the machine.

The result was audacious, visionary, unrelentingly experimental – dynamic in the most literal sense. The novel, Faulkner recognized right away, was a tour de force. And that force stemmed in no small part from the scene and circumstances of its composition: within the force field generated by industrial modernity.

It’s not every university that can claim to be the birthplace of an indisputably classic novel. Still fewer can boast, as the University of Mississippi can, that two such novels were created on its campus: Faulkner had also written “The Sound and the Fury” at his parents’ residence, the Delta Psi house.

The Delta Psi house was removed decades ago to make way for a new alumni center. The demolition of the power plant looms, so readers hoping to make tangible contact with a unique chapter in literary history had better hurry.

Jay Watson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

* This article was originally published at The Conversation

HELP STOP THE SPREAD OF FAKE NEWS!

SHARE our articles and like our Facebook page and follow us on Twitter!

0 Comments