The military draft has surfaced again as a source of national debate, as it has throughout American history.

On June 15, the Senate passed a proposal to require women to register with the Selective Service. In the same bill, Senator Rand Paul took the opportunity to introduce an amendment to eliminate the draft entirely.

As a Ph.D. candidate studying constitutional history in the North during the Civil War, I see the extension of the draft to women as something new. On the other hand, Paul’s opposition to national conscription is practically as old as the country itself.

Critics of the draft, from the first constitutional debates to the Civil War to World War I to Rand Paul today, have embraced the constitution to attack what they see as the antidemocratic nature of conscription.

Why has this debate gone on so long?

Divided at the root

Arguments for and against the draft are rooted in the Constitution, which granted Congress the power to raise armies. During ratification of the Constitution in 1788 and 1789, Anti-Federalists – those opposed to the Constitution as written – raised concerns over this power.

Their first and central claim was that the Constitution provided unlimited power to Congress over states’ forces. An Anti-Federalist author, Brutus, warned that if the national government needed to raise an army, it would directly force men from out of the state militias and into the national forces.

This idea was worrying to 18th-century Americans who had not forgotten the British army’s presence in the colonies in the lead-up to the American Revolution. Directly mustering individuals from state armies into a national army would destroy states’ ability to regulate their own militias, and thus their independence.

During the War of 1812, several New England governors refused to allow their citizens to be marched out of their states under conscription. They objected to the notion that the federal government had authority to use state militia. In December 1814, these governors proposed amendments at the Hartford Convention to stop conscription. The convention failed, but the Anti-Federalist constitutional arguments against usurping state militia power survived.

The first national draft

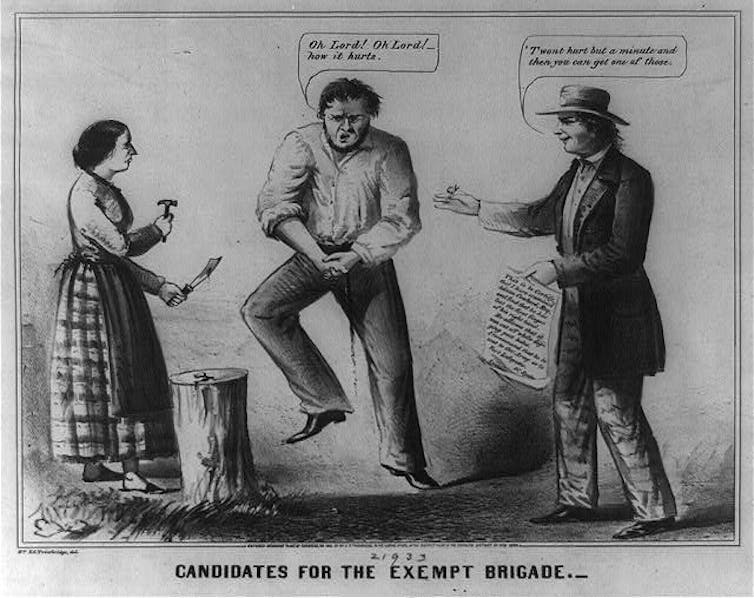

The Civil War was the first time in American history that national conscription of civilians took place, starting with the Confederacy in April 1862 and the North in March 1863. Before then, federal power had been limited to calling on citizens already in service of the United States, or in state militias.

The draft engendered fierce opposition from the Midwest to Pennsylvania, New York and New England. During the war, northern Democrats built upon existing constitutional arguments against conscription, primarily focused on opposing federalism.

To bolster their argument, northern Democrats argued states had a reserved right, under the Tenth Amendment, to maintain their militias. In their view, the Constitution delegated no right to the federal government to take absolute control over state militias, or to conscript individuals. In the Constitution, they argued, the word “army” did not encompass the militias of the states, or individuals not in service.

As one New York pamphleteer argued, individuals were now subjected to the “immediate domination of Federal powers.” The opposition managed to secure a few minor legal victories in Pennsylvania and New York. But no case ever reached the Supreme Court, where the draft could have been struck down.

National conscription created a massive federal administrative apparatus. Northern Democrats argued that the creation of the Provost Marshal and Board of Enrollments was unconstitutional because it vested independent judicial powers in unappointed executive officers. Such centralized administrative power is familiar to modern Americans, but the breadth of new federal power stunned 18th- and 19th-century Americans.

The legacy carries on

When national conscription was revived in 1917 after the United States entered World War I, constitutional arguments against it continued. Socialists who eventually brought a case before the Supreme Court argued the Thirteenth Amendment prohibited the draft as involuntary servitude.

However, in 1918, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld conscription in Arver v. U.S. The court refused to wrestle with the constitutional tradition against conscription because the power to draft was “clearly sustained” by the Constitution, according to Chief Justice Edward Douglass White.

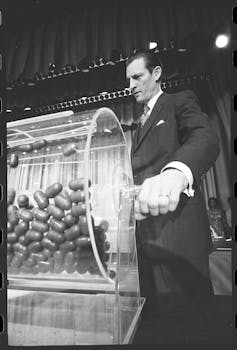

From World War I to the Vietnam War, the debate over the draft shifted focus from national power to free speech. Protesters demanded the right to publish anti-draft pamphlets and burn draft cards. Public opinion during Vietnam caused a shift to an all-volunteer army, but 18-year-old males are still required to register for the Selective Service. Soon, females may be required to do the same. That makes a modern-day draft still a real possibility.

And while the draft exists – even if it is rarely used – the arguments regarding conscription’s place in a constitutional democracy will likely continue as well.

Nicholas Mosvick previously worked as a legal associate for the Cato Institute.

* This article was originally published at The Conversation

HELP STOP THE SPREAD OF FAKE NEWS!

SHARE our articles and like our Facebook page and follow us on Twitter!

0 Comments